St James’ Church History

Being Sydney’s oldest church, St James’ plays an important part in the history and architectural heritage of Australia.

The Bicentenary Celebrations of St James’ 2019-2024

Many events are planned for the celebration of St James’ Bicentenary. These can be found on our What’s On page and in the calendar (search for ‘Bicentenary’ in List View).

Reconciliation Action Plan

The St James’ Parish Council has endorsed the development of a Reconciliation Action Plan, which will aim to fulfil the follow goal and objectives of the St James’ Strategic Plan 2021-2025 (Section 4):

- [to] Engage in dialogue with the Local Aboriginal Land Council regarding practical reconciliation activities;

- [to] Meet with representatives of the Local Aboriginal Land Council;

- [and to] Develop a practical reconciliation programme with indigenous people in Sydney.

A small working group has been established to work on the plan. More information will be added as it comes to hand, so check back regularly.

History and Architecture

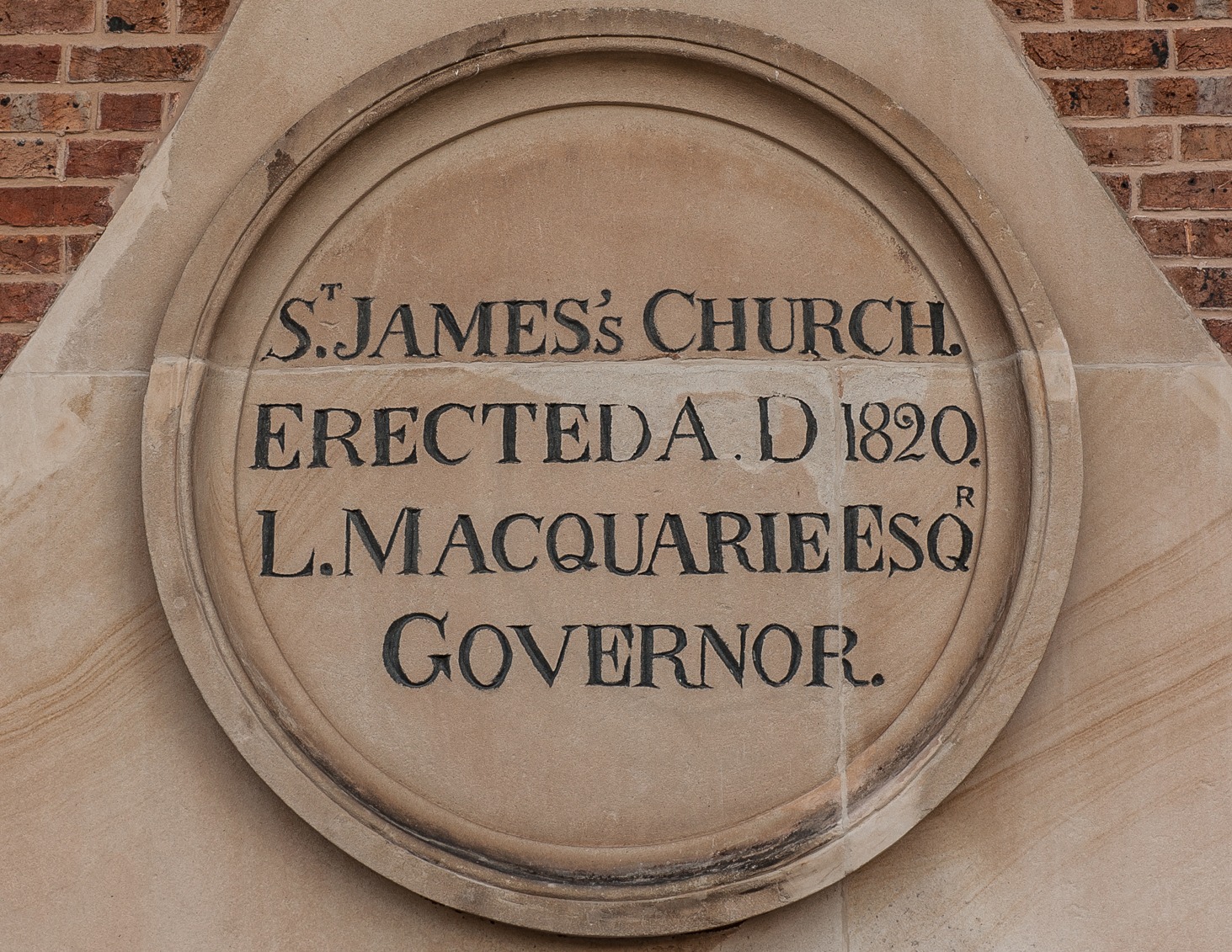

St James’ Church was constructed between 1819 and 1824. It is the oldest church building in the City of Sydney and has been in continuous use from its consecration on 11 February 1824 to the present.

The church came about through a series of unusual events. In 1819 convict and civil architect Francis Greenway was asked to design a courthouse for Governor Lachlan Macquarie. At that time, Macquarie’s plans encompassed a grand cathedral on George Street, and a courthouse and school on King Street. However, due to the recommendations of Commissioner Bigge, sent from London, the cathedral plans were put on hold, the school relocated, the planned school turned into the courthouse and the already commenced courthouse into a church dedicated to St James (the cathedral was not finished until 1868).

As a result, St James’ is a prime example of the architectural work of the Macquarie period, completely designed and built by convict labour. It is an integral part of the most extensive surviving group of Macquarie period buildings in Australia, which also includes the former Hyde Park Barracks, the (Old) Supreme Court, the General Hospital (the Mint and Parliament House) and Government House offices and stables (Conservatorium of Music). The church and the King Street Courts (formerly the Supreme Court) are the only buildings of this group to retain their original function.

The church contains a rare collection of 19th century marble memorials, its painted Children’s Chapel is unique in Australia and it includes amongst its collections and contents rare items of movable heritage. The original building has an extensive undercroft (called the Crypt) with sandstone walls, a central corridor and twelve brick barrel vaults.

Substantial modifications and additions have been made to St James’ since its completion in 1824 but without significant loss of character of the exterior as a Georgian town church. The interior of the church was totally remodelled in 1900–1902 and all earlier fabric removed with the exception of the 19th century memorials, some timber panelling and the basic retention of the western gallery. The form and contents of the interior of the church are essentially as designed and built in the early 20th century, with the exception of the Chapel of the Holy Spirit (south portico) which was rebuilt in 1988.

St James’ Church is significant in the history of New South Wales as:

- The second Anglican church in Sydney and now the oldest church building in the City of Sydney in continuous use for its original purpose since its consecration in 1824.

- A part of official buildings constructed for Governor Macquarie on the east side of Sydney, which were an important element of Macquarie’s town plan and improvements in Sydney.

- The church in which the first Bishop of Australia, W.G. Broughton, was installed in 1836 and the first church in which the Bishop regularly officiated.

- The church in which the first ordinations of Anglican clergy were held in Australia and classes held for the first theological college.

- For its role in education including the first attempt at kindergarten teaching in New South Wales.

- For its strong associations with the life and work of Francis Greenway, the Turramurra Painters, Bishop W.G. Broughton, Governor Macquarie and Commissioner J.T. Bigge, a continuing sequence of notable choirmasters, organists and organ builders who have contributed to the musical life of the church and the individuals and families commemorated in its memorials.

- For the quality of its original workmanship, its brickwork being ‘far superior to any in Colony’ on completion in 1824.

- As a fine example of Francis Greenway’s civic architecture.

- For the aesthetic quality of the murals in the Children’s Chapel, unique in Australia and a rare surviving example of the mural art of the Turramurra Painters, an unusual 20th century collaborative partnership of artists.

- For the form and construction of the Crypt unique in a Greenway building.

- For the rare collection of 19th century marble memorials.

For an external detailed history of the Church, please visit:

https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5054947

Archives

St James’ Church Registers prior to 1856 contain only minimal information. Unlike modern birth and death certificates they contain almost no details regarding antecedents.

For conservation reasons, the original registers are not generally available to researchers, nor can they be photocopied. An index to entries in the 19th century baptismal, marriage and burial registers is held in the Parish Archives. Research enquiries may be sent by letter or email to The Parish Archivist at:

St James’ Parish Office

Level 1, 169-171 Phillip Street

Sydney NSW 2000

archivist@www.sjks.org.au

A small charge may be made for this service. Please include your full name and contact details (including postal address) with all research enquiries.

Please refer to the information below before contacting the Archivist.

NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages www.bdm.nsw.gov.au

Prior to the introduction of civil registration in New South Wales in 1856, the only official records of baptisms, marriages and burials were those kept by the clergy. Some years after civil registration began, many of these early church records were transcribed for the Registrar General’s Department in an attempt to provide a full record, for legal purposes, of all baptisms, marriages and burials recorded in the Colony prior to 1856.

The New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages website has online indexes for the following records:

Births 1788–1905

Deaths 1788–1945

Marriages 1788-1945

Family History Certificates

Copies (called Family History Certificates) of ‘Unrestricted Records’ may be purchased from the Registry. The ‘Unrestricted Records’ are:

Births 1788–1905

Deaths 30 years ago or more

Marriages 50 years ago or more

It is important to remember that the pre-1856 Family History Certificates provided by the Registry are transcriptions of the original early church records. Difficulties in deciphering handwriting mean that there may be errors in some of these Certificates. In some cases, information that is important to family historians was omitted from the transcriptions (for example, ship of arrival). Researchers should check the microfilm copies of original records, wherever possible, to verify the accuracy and completeness of the information provided in Family History Certificates.

The Parish of St James

When a baptism, marriage or burial is described as having taken place in the ‘Parish of St James’ this does not necessarily mean that the ceremony in question was performed in St James’ Church, but only that it took place in the geographical parish of St James. The boundaries of the Parish of St James, which occupies the north-eastern quarter of the City of Sydney, have remained essentially unchanged since the parishes were first mapped in the mid-1830s.

There were, and still are, places of worship of several religious denominations within the Parish of St James, including St Mary’s Cathedral, St Stephen’s Uniting Church and the Great Synagogue. In the early 19th century there were, in Macquarie Street alone, a synagogue; a Friends’ (Quakers’) Meeting House and a Wesleyan Meeting House. These were all in the ‘Parish of St James’.

Baptisms

Baptisms 1824–1924

The St James’ baptismal registers record:

- the name of the person baptised

- their date of birth, or age

- the date of baptism

- their parents’ first names and surname (but not the mother’s maiden name)

- the father’s profession

- the family’s place of residence at the date of baptism

The names of godparents or sponsors are not given and there are no details of the parents’ date and place of marriage. Baptisms were sometimes performed privately (at home) if it was thought likely that the child might die before they could be brought to church. The notation ‘PB’ in the registers means ‘Private Baptism’. If the child survived, they would then be ‘received’ into the church at a later date.

Microfilmed Baptism Records

The baptism, marriage and burial registers of the church are a valuable source of information for family historians. They are however very fragile and, for conservation reasons, are not generally available to researchers; nor may they be photocopied. In order to make these registers available for research, while ensuring their preservation, various records have been microfilmed.

The following St James’ baptism records have been microfilmed:

Baptisms 11 February 1824 to 21 December 1924*

*Records after this date are not currently available for general research.

These microfilms are available at:

The Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Macquarie Street, Sydney

The Society of Australian Genealogists, Richmond Villa, 120 Kent Street, Sydney

The Society of Australian Genealogists’ (SAG) Reel Numbers for the microfilmed St James’ Church records are given for ease of reference and are as follows:

BAPTISMS

SAG Reel 61 Baptisms 1824–1825

SAG Reel 62 Baptisms 1826–1835

SAG Reel 136 Baptisms May to June 1835

SAG Reel 61 Baptisms 1835–1854

SAG Reel 86 Baptisms 9 July 1854 to 21 December 1924

Marriages

Marriages 1824–1963

In the early 19th century in New South Wales, couples (other than convicts) could be married either by banns or by license, following the usual practice in England.

Marriages by banns 1824–1864

To be married ‘by banns’ a couple’s intention to marry was ‘published’ (that is, read out) in their home parishes on three successive Sundays during the course of the main service, which was usually Morning Prayer. The Minister would read out the names of the man and woman, their marital status (bachelor, spinster, widower or widow), the parish they lived in, their intention to marry and would then say to the congregation, “If any of you know cause, or just impediment, why these two persons should not be joined together in Holy Matrimony, ye are to declare it”.

This custom was an effective means of checking the validity of proposed marriages in pre-industrial England, when the majority of the population lived in the same locality all their lives. Their neighbours and close relations, who would usually live nearby and attend the same church, would know if they were free to marry or whether there were any ‘impediments’ to the proposed marriage (for example, a previous marriage with the other partner still living, or a prohibited degree of consanguinity).

If there were no objections, then the marriage could proceed. When the intended marriage did not take place, the reason is noted in the banns book.

Because the banns had to be called in the home parish of both parties, the St James’ Banns Books include the publication of banns for couples who were then married in another church. This is noted in the book, for example, ‘Married at Liverpool’.

In New South Wales, the consent of the Governor was required for the marriage of all convicts still under sentence. The convict indents were checked to verify the person’s marital status on their arrival in the Colony. Those who had been listed as married on arrival could not remarry unless conclusive proof could be provided of the subsequent death of their spouse. Assigned convicts also had to have the consent of the person to whom they were assigned. In some cases, the parties themselves changed their minds and withdrew from the proposed marriage. Other marriages were ‘forbid’ because objections were notified to the clergy.

The St James’ Banns Books cover the period from March 1824-September 1864. From 1824 to 1847 the Banns Books may include information that is not given in the marriage register, for example the ship on which a convict was transported, the person to whom they were assigned and whether they were free, freed by servitude, or held a ticket of leave. From 1848 the entries consist only of the names of the parties and the dates on which the banns were called. Banns were last called at St James’ Church on 11 September 1864. The custom has died out in Australia but is still in use in the Anglican church in England.

Marriages by license 1824–1963

Being married by license was more expensive than being married by banns but permission to many was granted more quickly and, unlike calling the banns, the parties to the marriage did not have to be resident in the parish prior to the wedding. The cost of the license made it somewhat more prestigious than being married by banns. It was also a more private way of applying to be married. For many migrants who did not have friends and family in the Colony, marriage by license was more appropriate than the familial custom of calling the banns.

Marriage declarations 1870–1892

These forms were filled out by the couple before the marriage and usually contain the same information as that given in the marriage register.

Microfilmed Marriage Records

The baptism, marriage and burial registers of the church are a valuable source of information for family historians. They are however very fragile and, for conservation reasons, are not generally available to researchers; nor may they be photocopied. In order to make these registers available for research, while ensuring their preservation, various records have been microfilmed.

The following St James’ marriage records have been microfilmed:

Banns of marriage 7 March 1824 to 11 September 1864

Marriages 27 February 1824 to 24 August 1963*

Marriage declarations 1870–1892

* Records after this date are not currently available for general research.

These microfilms are available at:

The Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Macquarie Street, Sydney

The Society of Australian Genealogists, Richmond Villa, 120 Kent Street, Sydney

The Society of Australian Genealogists’ (SAG) Reel Numbers for the microfilmed St James’ Church records are given for ease of reference and are as follows:

MARRIAGES

SAG Reel 62 Banns of marriage 1824–1864

SAG Reel 61 Marriages 1824–1825

SAG Reel 62 Marriages 1826–1835

SAG Reel 136 Marriages November 1835 to January 1839

SAG Reel 61 Marriages 1839–1853

SAG Reel 64 Marriages 1853–1858

SAG Reel 65 Marriages 15 May 1858 to 9 December 1892

SAG Reel 136 Marriages December 1892–1915

SAG Reel 137 Marriages 28 August 1915 to 18 April 1925

SAG Reel 66 Marriages 18 April 1925 to 12 February 1934

SAG Reel 67 Marriages 24 February 1934 to 22 February 1947

SAG Reel 68 Marriages 28 February 1947 to 24 August 1963

SAG Reel 62 Marriage declarations 1870–1877

SAG Reel 63 Marriage declarations 1877–1884

SAG Reel 64 Marriage declarations 1884–1892

Burials

For much of the 19th century, the burial service was usually read, in part, in the residence of the deceased, followed by the committal at the graveside. In the majority of cases there was not a funeral service in the church, as we know it today.

Government records show that the clergy in Sydney worked on a roster system for officiating at burials in the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s. As burials usually took place within a day or so of a death (and in some cases on the day of death) this was quite an onerous and time-consuming job, as the minister had to be on call at short notice to read the burial service.

Each minister would enter the burials that he had conducted during his rostered turn of duty in his church’s burial register. This means that the presence of a particular minister at a burial cannot be taken to imply that the deceased was one of his parishioners, or was even resident in his parish. The St James’ burial registers are continuous from February 1824 to December 1849. From 1850 to 1856 only twenty burials were recorded. The register ends on 9 August 1856. The civil registration of births, marriages and deaths began in 1856.

Place of burial is not recorded in the burial register. St James’ Church has never had a burial ground. The columbarium in the crypt of the church, which is reserved for the deposition of parishioners’ ashes, came into use in 1930.

Cemeteries in Sydney and its suburbs

Much useful information about cemeteries in Sydney and its suburbs is provided in the book Sydney Burial Ground 1819–1901 (Elizabeth and Devonshire Streets) and History of Sydney’s Early Cemeteries from 1788 by Keith A. Johnson and Malcolm R. Sainty, published in 2001 by the Library of Australian History. Appendix 4 of this publication lists all of the cemeteries in the Greater Sydney region, in chronological order, and Appendix 5 gives their location, name, modern place name and the date when each came into use, together with other remarks (e.g. ‘Still in use’).

The main Sydney cemetery for much of the 19th century was the Devonshire Street Cemetery at what was then the southern extent of the town. This was used from 1819 until it was closed in 1888 and was totally removed in 1900 to build the present Central Railway Station. The bodies were exhumed and moved to other cemeteries. The documentary records of the cemetery are incomplete and by the time it was moved many headstones had decayed or been damaged and were indecipherable. Many burials would never have had headstones and so the remains could not be individually identified.

The history of the cemetery, its removal and the relocation of the remains to other cemeteries are fully explained in Sydney Burial Ground 1819–1901 (Elizabeth and Devonshire Streets) and History of Sydney’s Early Cemeteries from 1788 by Keith A. Johnson and Malcolm R. Sainty. The book also includes indexes to all of the surviving documentary records of the Devonshire Street Cemetery and the monumental inscriptions transferred to Bunnerong and transcribed by the authors in 1969.

Further information about cemetery records and much useful guidance for family historians is available from The Society of Australian Genealogists, Richmond Villa, 120 Kent Street, Sydney, NSW 2000. Its website is www.sag.org.au.

Monuments and Memorials in St James’ Church

St James’ Church has a fine collection of 19th century marble memorials that commemorate notable members of Colonial society as well as regular worshippers. The 20th century memorials commemorate the lives of parishioners.

Microfilmed Burial Records

The following St James’ burial records have been microfilmed:

Burials 29 February 1824–1856

* Records after this date are not currently available for general research.

These microfilms are available at:

The Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Macquarie Street, Sydney

The Society of Australian Genealogists, Richmond Villa, 120 Kent Street, Sydney

The Society of Australian Genealogists’ (SAG) Reel Numbers for the microfilmed St James’ Church records are given for ease of reference and are as follows:

BURIALS

SAG Reel 61 Burials 1824–1825

SAG Reel 62 Burials 1826–1834

SAG Reel 136 Burials 1834–1838

SAG Reel 61 Burials 1839 to 9 August 1856

SAG Reel 68 Burials 22 Dec 1845 to 28 July 1846